In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the world experienced an ephemeral respite to the chaos caused by the initial wave of viral spread. Countries such as China, India, and the United States took drastic steps to stop the spread of the virus culminating in a near complete shutdown of our daily routines. In attempts to provide any resemblance of good news, media outlets published stories detailing how heavily polluted cities like Beijing, New Delhi, and Los Angeles, usually laden with layers of smog, were clearing. The global carbon dioxide emissions reduced from 100 million metric tons by 17% (1). These short weeks of quarantine provided a glimpse of the true beauty of our world; behind the curtain of pollution, we saw the deep blue skies and crystal-clear waters that were hidden away.

Unfortunately, the world could not persist under a complete city shutdown. Factories resumed their production, bringing with them as much as 100 million metric tons of harmful emissions per day. The smog returned to pre-COVID-19 levels over several months, redrawing the curtain over our glimpse of clarity (2). Could these changes really have caused such a dramatic effect on such a short time scale? This pattern is in fact reminiscent of the environmental changes leading up to the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, when in order to reduce the amount of pollution in the city, Beijing restricted daily traffic and factory production. These changes improved the air quality conditions in the city, but the pollution returned following the Olympics. The direct consequences of our lifestyles have been illustrated to us time and time again. We must now use this experience as an opportunity to appreciate both the long term and immediate consequences we have on the environment and its climate.

Changes for the future can be difficult to imagine because of our draw for immediate returns. However, with the increasing rate of natural disasters, including a historically prolific hurricane season already (3), we are witnessing the effects of our negligence. The future that climatologists have predicted and worried about is here. Yet, the glimpse of our world that COVID-19 showed us has the potential to be our reality. By relying less on transportation to work and halting production from coal-burning factories, we experienced altered lifestyles that are less dependent on fossil fuels. Our current way of life creates enough traffic to cause cars to come to a standstill twice a day. However, by making permanent changes to work from home and use renewable resources, we can drive significant changes to our climate.

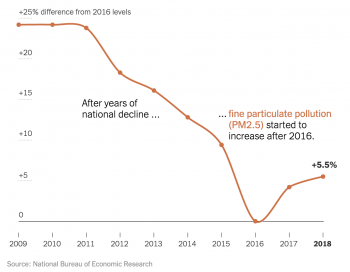

It is possible that the emphasis on the long-term effects of climate change has allowed deniers and naysayers to ignore and oppose the actions necessary to counter the rising temperatures, melting ice caps, and increasing severity of natural disasters. If we can learn one thing about our climate during this pandemic, it is that our choices can instigate immediate change when we all do our part. Reduction of smog-inducing pollutants like nitrogen dioxide emissions and particulate matter of 2.5 microns in size (PM2.5) is something that can be achieved now. In time, these changes can also reduce carbon dioxide levels, a long-lasting contributor of greenhouse gasses and the rising global temperatures. Strikingly, past restrictions, including the Clean Air Act, were effective at reducing total emissions, and when these restrictions were lifted, the level of damaging emissions increased, as noted by the total levels of PM2.5 spanning a transition of federal leadership.

Levels of PM2.5 pollution across the last decade (4).

If all you want is nothing else but more days of clear blue skies, then that is reason enough to care about the current level of pollution. Light scattering among particles in the atmosphere alters the observed color of the sky. These particles can come in the shape of pollution or even dust, ash, and humidity. The more particles present, the more light is scattered, leading to dull, grey skies. For example, in the mountains around Denver, the high elevation reduces the area where light can be scattered among these particles, and in the deserts of New Mexico, the dry air contains less condensed water vapor, meaning that there are fewer particles of this nature to scatter the light. Thus, in both of these regions, shockingly blue skies can be seen (5). While elevation and humidity are largely out of our control, air pollution is a large contributor to light scattering particles. So, maybe the skies of St. Louis can achieve striking, picturesque skyscapes through us making smarter choices for both our immediate health and happiness, as well as that of our Earth.

1 – https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-020-0797-x

2 – https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/09/05/air-pollution-is-returning-to-pre-covid-levels

3- https://www.noaa.gov/media-release/extremely-active-hurricane-season-possible-for-atlantic-basin

4 – https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/10/24/climate/air-pollution-increase.html

5 –https://www.desertmuseum.org/books/nhsd_desert_air.php#:~:text=Sonoran%

20Desert%20skies%20are%20such,particles%20and%20droplets%20called%20aerosols.